Gastroshiza, also known medically as gastroschisis, affects approximately 1 in 5,000 newborns worldwide. This congenital condition involves an opening in the abdominal wall that allows intestines and sometimes other organs to protrude outside the body. While the diagnosis can feel overwhelming for expecting parents, understanding this condition helps families prepare for treatment and recovery.

The term “gastroshiza” comes from medical terminology, though gastroschisis remains the standard clinical name. Both terms describe the same condition where the baby’s abdominal wall doesn’t fully close during fetal development, creating a hole typically located to the right of the umbilical cord.

Understanding Gastroshiza: What Parents Need to Know

Gastroschisis occurs when the abdominal wall fails to close completely during the first trimester of pregnancy. The CDC defines gastroschisis as “a birth defect where there is a hole in the abdominal (belly) wall beside the belly button. This results in the baby’s intestines extending outside of the baby’s body.”

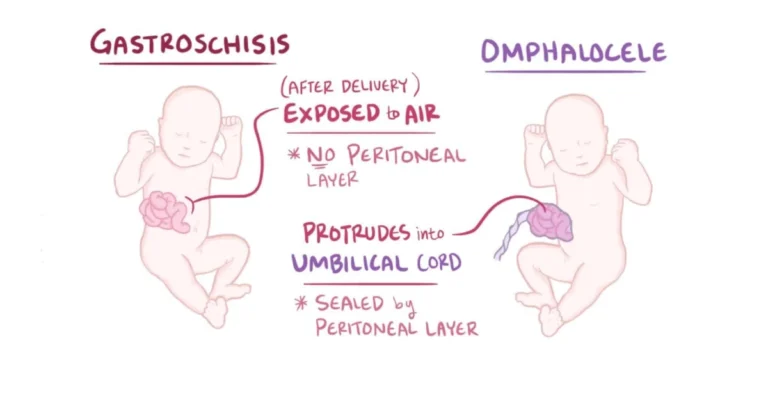

Unlike omphalocele, another abdominal wall defect, gastroschisis doesn’t involve a protective membrane covering the exposed organs. The intestines float freely in the amniotic fluid throughout pregnancy, which can cause irritation and complications.

This condition differs significantly from other birth defects because it is rarely associated with chromosomal abnormalities or genetic syndromes. According to StatPearls, gastroschisis “is rarely associated with genetic conditions,” making it primarily an isolated developmental occurrence.

Primary Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of gastroschisis remains unknown, but researchers have identified several contributing factors. Texas Children’s Hospital explains that gastroschisis “is believed to be caused by disruption of the blood supply to the abdominal wall during fetal development, preventing it from closing all the way.”

Maternal age plays a significant role in risk assessment. Young mothers, particularly those under 20, show higher rates of babies born with gastroschisis. Environmental factors also contribute to increased risk, including maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and exposure to certain medications during early pregnancy.

Nutritional deficiencies, especially inadequate folic acid intake before conception and during early pregnancy, may increase the likelihood of developing abdominal wall defects. Geographic clusters of gastroschisis cases suggest environmental factors may influence occurrence rates.

Socioeconomic factors indirectly affect risk levels. Limited access to prenatal care, poor nutrition, and exposure to harmful substances often correlate with higher birth defect rates in certain populations.

Prenatal Diagnosis and Detection Methods

Most cases of gastroschisis are diagnosed through routine prenatal ultrasounds performed between 18-22 weeks of pregnancy. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia states that “gastroschisis is diagnosed by routine ultrasound in the second trimester when free-floating intestine is seen.”

Advanced ultrasound technology allows healthcare providers to visualize the floating intestines and assess the severity of the condition. Three-dimensional ultrasounds provide detailed images that help surgical teams plan treatment approaches before birth.

Additional diagnostic tests may include amniocentesis to check for chromosomal abnormalities, though these are rarely found with gastroschisis. Maternal blood tests measuring alpha-fetoprotein levels often show elevated results when fetal abdominal wall defects are present.

Regular monitoring throughout pregnancy tracks fetal growth and identifies potential complications. Some cases may show signs of intestinal damage or growth restriction, requiring specialized delivery planning.

Treatment Approaches and Surgical Options

Immediate surgical intervention becomes necessary after birth to protect the exposed intestines and close the abdominal wall defect. Cleveland Clinic emphasizes that “surgery is necessary to replace your baby’s organs inside their body after birth.”

Two main surgical approaches treat gastroschisis: primary closure and staged repair. Primary closure involves placing all organs back into the abdomen and closing the wall in a single operation. This approach works best when the abdominal cavity can accommodate the organs without creating excessive pressure.

Staged repair becomes necessary when the abdominal cavity is too small to hold all the organs safely. Surgeons use a temporary covering called a silo to gradually reduce the organs back into the abdomen over several days or weeks.

Pre-surgical care in the neonatal intensive care unit focuses on protecting the exposed organs, maintaining body temperature, and providing intravenous nutrition. The intestines are carefully wrapped in sterile, moist dressings to prevent infection and dehydration.

Post-surgical monitoring addresses potential complications, including infection, feeding difficulties, and intestinal blockages. Most babies require several weeks of hospital care before discharge.

Potential Complications and Long-term Outcomes

Johns Hopkins Medicine notes that gastroschisis can lead to “irritation and swelling, as well as a shortening of the intestine” due to exposure to amniotic fluid. These complications can affect digestive function and require ongoing medical management.

Short bowel syndrome represents one of the most serious complications, occurring when prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid damages intestinal tissue. This condition may require specialized nutrition support and additional surgical procedures.

Feeding difficulties commonly affect infants with gastroschisis. The intestines may not function normally initially, requiring intravenous nutrition until normal feeding patterns develop. Some children experience ongoing digestive issues, including reflux, constipation, or food sensitivities.

Adhesions, or scar tissue formation, can cause intestinal blockages later in life. These may require additional surgical interventions to restore normal bowel function.

Despite these challenges, the overall prognosis remains positive. The CDC reports that survival rates exceed 85-90% with appropriate medical care. Most children with gastroschisis lead healthy, normal lives with proper treatment and follow-up care.

Prevention Strategies and Prenatal Care

While gastroschisis cannot be completely prevented, certain measures may reduce risk factors. Taking 400 micrograms of folic acid daily before conception and throughout early pregnancy supports healthy fetal development and may reduce birth defect risks.

Avoiding harmful substances during pregnancy is crucial. This includes eliminating tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs, as well as carefully managing prescription medications with healthcare providers.

Maintaining a healthy weight before pregnancy and eating a balanced diet rich in vitamins and nutrients supports optimal fetal development. Regular prenatal care allows early detection of potential problems and provides opportunities for intervention.

Young mothers should receive additional support and education about healthy pregnancy practices. Access to comprehensive prenatal care, nutritional counseling, and social services can help address risk factors associated with gastroschisis.

Living with Gastroshiza: Family Support and Resources

Families affected by gastroschisis often benefit from connecting with support groups and other families who have experienced similar challenges. These connections provide emotional support, practical advice, and hope during difficult periods.

Long-term follow-up care involves regular check-ups with pediatric specialists to monitor growth, development, and digestive function. Some children may require additional surgeries or interventions as they grow.

Educational support may be necessary if complications affect learning or development. Early intervention services can help address any delays and support optimal outcomes.

Financial planning becomes important due to ongoing medical costs. Many insurance plans cover necessary treatments, but families should understand their benefits and seek assistance when needed.

FAQs

What is the difference between gastroshiza and gastroschisis?

Both terms refer to the same condition – a congenital abdominal wall defect where intestines protrude outside the body.

How common is gastroschisis?

Gastroschisis occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 births, and rates have been increasing in recent decades.

Can gastroschisis be detected before birth?

Yes, routine prenatal ultrasounds typically detect gastroschisis during the second trimester of pregnancy.

What is the survival rate for babies with gastroschisis?

Survival rates exceed 85-90% with proper medical care and surgical intervention.

Will my child need multiple surgeries?

Most children require only the initial repair surgery, though some may need additional procedures for complications.

This article was medically reviewed by board-certified pediatric specialists and is based on current clinical guidelines and research. Always consult with healthcare providers for personalized medical advice.